Review by Bhupinder Singh

The Man Who Bent Light by Narinder Singh Kapany

Roli Books, 2021, ISBN: 978-81-952566-0-0

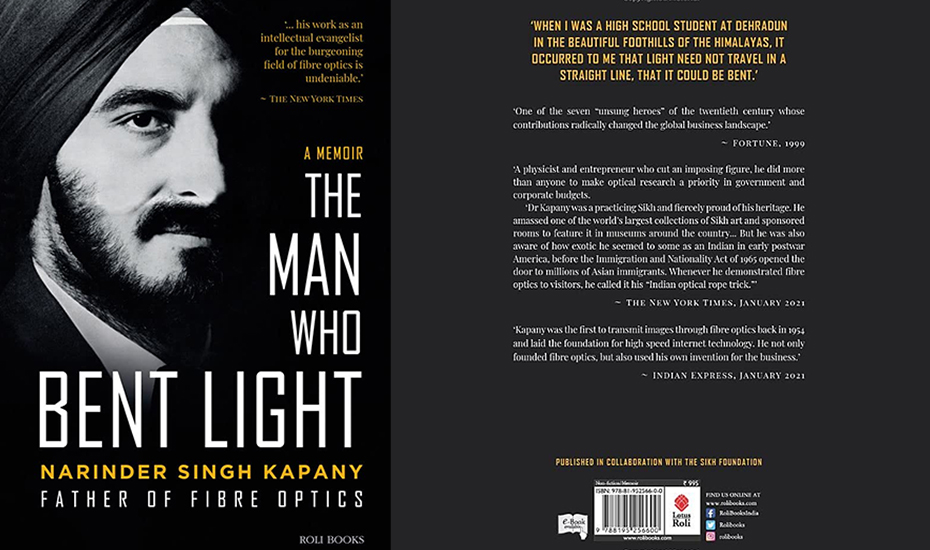

We can all remember being taught in schools that the light travels in a straight line, accepted it as the universal truth, and it is firmly ingrained in our minds. But there was someone who was not willing to accept this axiom, and his dogged determination to prove it otherwise, unleashed a new field of study called ‘Fiber Optics’ and he became known as its father. He was not just a scientific trailblazer, but also had a rare privilege of writing his own autobiography. So, such a unique combination makes this book “The man who bent light” by Dr. Narinder Singh Kapany an interesting read on a fascinating life.

Dr. Kapany was born on October 31, 1927.

There are 12 Parts in the book. The entire book covers all the phases of Dr. Kapany’s life starting from Boyhood and ending in Family Matters. The author claims that he captured “memorable moments and scenes” from his life at the behest of his son and daughter. It is amazing that even in his nineties he could recall in detail the scenes from his early childhood, when he was three.

In the first Chapter titled Property describes in detail the young Narinder overhearing his Grandmother Manji discussing their ancestral property with Aunt Nuntal. The sight of the vast land mass made him wonder “How can one family possess so much?” The next Chapter Sodhi-wala describes the journey on a wagon drawn by two white bullocks when one-wheel careens off making him and his older brother fall to the wagon floor and both of them fall into half-sleep. In the next Chapter Ring the author shares a fascinating story of a ‘lucky ring’ which his father got from a Russian woman for helping her to safety during World War 1. His mother gave this ring to him as a good luck charm, when his name was not on the newspaper list of people who had successfully passed the college degree. The ring’s charm surely seems to have worked as next day the newspaper carried an apology along with an amended list for the omissions from the list released in the day earlier. Sure enough, his name was on the top of this revised list.

The Chapter ‘Here Bino, take my hand’ describes how he as a kid of 6 or 7 was awestruck by the sheer size and the magnificence of Darbar Sahib (also known as Golden Temple). There, her mother urged him to ‘Go with your father’ into the holy water sarovar for a dip. The Chapter ‘Stolen Fruit’ is not just a tale of a childhood prank, but that enkindled a pride of being a Sikh in him. The Chapter ‘Almost True Stories’ details how two volumes of Janam Sakhis of Guru Nanak Dev Ji inheritance of the family nurtured the taste of exquisite art which germinated the idea of becoming a collector and giving it a lasting home in the form of San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum. The Chapter ‘Chain Reaction’ beautifully captures the faith of the teacher Mr. Zacharich in his pupil Narinder, despite his naughty pranks in the school in Dehradun. The Chapter ‘Deadheading’ captures the faith of the father in his blossoming son when he says that “I’m certain you’ll discover something valuable.” Narinder’s insight that “we weren’t carrying a load home” helped his father double the income. The Chapter ‘Partition’ besides sharing some details of the carnage that took place also shares a vital insight “So powerful and effective was Ranjit’s Singh rule that the British knew they could do nothing to change it;” which lay crumbled after his death.

The Chapter ‘Obsessed’ shares how the Professor’s statement in the classroom that “Light can travel in a straight line” not just woke up Narinder from his nap but seared him to the core and set him for life’s work and on a mission to prove otherwise. After graduating from the college, he joined the ordnance factory where he expressed to his boss his desire; “I want to learn everything I can about light. About optical instruments.” That same impulse took to him in 1952 to Imperial College in London where he met Professor Harold Hopkins, his mentor. Narinder and his Professor were both obsessed by the idea “that light and images could be transmitted through flexible axes.” There he met Satinder whom he eventually married in 1954 at Shepherd’s Bush Gurudwara, London in a Sikh wedding ceremony. He took a position of a Researcher with Bart & Stroud, Glasgow for few rainy months. But the lure of furthering his research and a PhD with full scholarship, including a stipend for personal expenses from Dr. Hopkins brought him back to Imperial College. Here he was re-obsessed setting up a laboratory to conduct experiments at age 25. As a part of his research, he had black mask with cut-out the word ‘Fibre’ taped to the lens and switched the light source. There it was on the screen in a single line of the letters Fibre – Bingo a successful experiment – the light has been bent. This test was featured as Rope ‘Scope in the September 1955 issue of the Popular Mechanics – a scientific journal.

He completed his course in PhD with 3 years of basic research and 6 months to author his thesis and prepare for the orals. The Chapter ’80-Pound Car’ details his sojourn to an international optics conference in Florence, Italy; with his wife and two friends in a car from London. His pioneering research had already garnered a great deal of interest in fiber optics field. The organizers had allotted a 15-minute time slot for his presentation, but with the heightened interest from the attendees he was given 40 minutes to fill, which he did. Here Dr. Robert Hopkins from University of Rochester, NY asked them out for lunch. He first asked Narinder what his future plans were, before offering him to come to the USA and further his research. He came to NY on a ship and his period there was a “Very Good Year” for his research as well as an opportunity to collaborate with doctors of John Hopkins University. His team’s pioneering work presented at the meeting of Optical Society of America in 1956 at Lake Placid, New York. It was there Dr. Leonard Reiffel, managing director of the Physics Department at Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago; offered him to come and work for him. In the Summer of 1959, about 3 years into what was an initially agreed to a two-year stay, Narinder with his family embarked on an extended vacation. He says that period in Chicago was the most productive period of his career.

The phone call from Maharaja Yadavindra Singh of Patiala, asked him to come to NY for an urgent meeting. There he met India’s Defense Minister Krishna Menon; who offered him to become his scientific advisor. After few months interval he went back to India on a vacation. There he had an hour’s meeting with the Prime Minister Nehru, which in his own words was most refreshing and personally rewarding hour. This offer for the position of scientific advisor was approved by Nehru, but the official appointment papers arrived after a year. India’s loss turned out to be America’s gain, as Narinder decided to set up his own venture Optics Technology in Palo Alto, near San Francisco. Here, they developed Endoscopes to look at the insides of everything. This was followed by the development of laser eye surgery and card readers using fiber optics. Interestingly these initiatives were underwritten by NIH to the tune of $ 250,000 a year for the first time. The trail blazing additions were Retinal Coagulation, Cardiac Oximeter, and HeNe (Helium-Neon) laser. As a side note, I would like to add here that during Covid-19 pandemic everyone in the world has used the Oximeter to detect Oxygen levels.

In 1970 while he was looking for something new to excite him, on a tour of his own facility he uncovered a piece of discarded cluster of fiber optics cables in a trash can. He picked it up excitedly and took it home, transforming it into a sculpture and named it “The Caged Serpent.” Now a new initiative was blossoming and soon he had made some more sculptures. Somehow the word got out to Frank Oppenheimer from S F. Exploratorium who called him and envisaged an interest in looking at the creations. Impressed after the tour of exhibits at Narinder’s house he proposed that they hold an exhibition of his creations. The fun thing done by Narinder as a hobby had garnered a new name called “Dynoptic” from Oppenheimer. His sculptures were first displayed in a one-man show at the Exploratorium of the Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco in 1972. In 1973 he sold his share of the company to his colleagues at the Young Presidents Organization (YPO). Looking for new gigs, an opportunity for posting as the second-in-command to the incoming US ambassador to India, Danial Moynihan opened up, however it failed to materialize.

In late 1973 he found himself in a situation where he had leisure to explore the world for other provocative opportunities. The backseat of a taxicab in Paris proved to be the place of birth of a new company which was called Kaptron with a major French telecommunication firm. That venture soon blossomed into a thriving telecommunications device designer and a manufacturer. He sold Kaptron in 1975 second time to AMP Inc. In 1975 he was invited to spend 6 months at the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) as Regents Professor. This tenure is offered to those who bridge the academic and non-academic worlds. With his turban, long beard, and deep voice; his was not a low-profile appointment. As the Regent he gave public lectures on innovation, productization of ideas, creativity, productivity, and entrepreneurship. At the end of 6 months when Narinder went to visit university’s chancellor Robert Sinsheimer to say goodbye, but he was not ready bid him goodbye. Narinder asked for months’ time and came back to him with a proposal for Center of Innovation and Entrepreneurial Development (CIED), pronounced ‘seed.’ He stayed as the Director of the center for 7 years which were some of the most gratifying times of his professional life.

The Part VI titled ‘Farming’ appears like a regression from innovative technology of Fiber Optics. But soon he discovers; “that science was a lot less complex than human relationships.” However, the notion technical regression is soon put to rest as he says that; “Again not to work the soil, but to be part of the growing process.” From a young boy pilfering oranges from the Maharaja Bhupinder Singh’s orchard in Patiala, to owning farms growing fruits in California valley reflects the passion of the person obsessed with a notion of bending the light. The Chapter ‘Wine and Oil’ makes an interesting read on his purchase of three thousand acres of an old vineyard in the central valley near Fresco, CA. How luck favored this man of science can be gauged from the fact that not only did he and his partners got the mineral rights for this parcel of land, but also mineral rights on an additional seven thousand acres. To me this is like Maida’s touch, where all investments turned into gold. Within 2 years the investment was earned back, thanks to the oil well’s royalty.

The Part VII titled ‘Being Sikh’ enshrines his unique contribution in setting up Chair on Sikh Studies-Department of Religion UCSB, Santa Barbara; Chair on Optoelectronics-UCSC, Santa Cruz; Chair on Entrepreneurship- UCSC, Santa Cruz. He also became an avid art collector of ‘Sikh Art’, the term he coined to describe unique Sikh art. The collection found a permanent house at the Asian Art Museum called Satinder Kaur Kapany Gallery in honor of his wife. All these efforts gave birth to a book called Sikh Art from Kapany Collection. The Sikh Foundation that he was instrumental in setting up back in 1967, celebrated its 50th anniversary with a special program from 5th to 7th May in 2017. In Part IX and X, he describes his yearning for a home in London and being selected as a Fellow of Royal Academy of Engineering- quite an honor. Besides the above-mentioned Fellowship, he was associated with Young President’s Organization (YPO), Cosmos Club, and National Invention Council (NIC).

The Part XI titled ‘Massacre’ makes a very tragic reading on how the Indian Government attacked the Darbar Sahib (Golden Temple) complex and other holiest Sikh shrines on June 3rd, 1984. By the end of the year 1984, about six thousand Sikhs had succumbed to the violence and prejudice in India. Unfortunately, his mother passed away in India and his visa application was refused and he could not attend her funeral. The last Chapter titled ‘Family Matters’ shares some details of family vacations and the passing of his wife Satinder from Parkinson on June 25th, 2016. He completed the writing of this autobiographical account in March 2020.