Legacy of the Sikh Foundation – The First Fifty Years

By Sonia Dhami

1967 America: Vietnam War continues and peace rallies intensify – Muhammad Ali stripped of his boxing championship for refusing the draft – World’s first heart transplant – The first ATM– Strikes by U.S. teaching staff for pay increases – The first Super Bowl, played between Green Bay Packers and the Kansas City Chiefs– Six-Day War in which Arab forces attack Israel – American cities, including Detroit, exploded in rioting and looting – “Summer of Love” with young people smoking pot and grooving to the music of the Grateful Dead – Color TVs become cheaper and more popular… thepeoplehistory.com

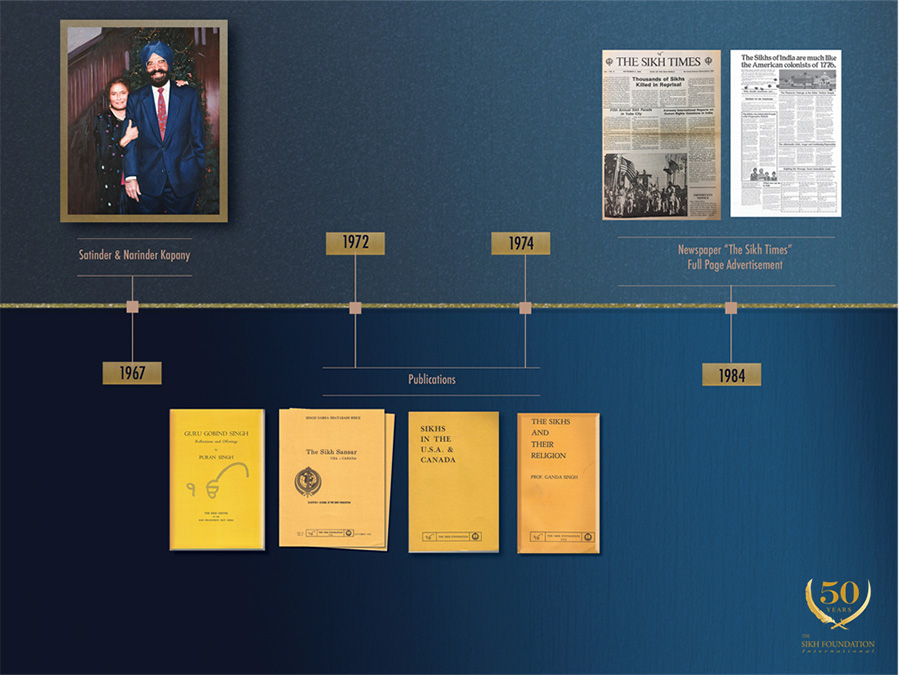

1967 was also the year when a young Sikh physicist, Narinder Singh Kapany, took his Silicon Valley optics company public and achieved the American dream. His dream was not just for himself. It also included his community. With immense pride, commitment, and faith in their Sikh heritage, he and his wife, Satinder, founded the Sikh Foundation in California on December 29, 1967, with the mission to preserve and promote Sikh heritage. Before setting up the foundation, both Narinder and Satinder were active members of the small Sikh community in Chicago, where he was also the president of the journal Sikh Study Circle of USA. In 1960 they moved to the San Francisco Bay Area and continued to support Sikh community activities, including the 1967 publication of a book titled Guru Gobind Singh – Reflections and Offerings, by Prof. Puran Singh. That same year, they established the Sikh Foundation in Silicon Valley, whose landscape at the time was vastly different from what we see today. The nearest gurudwara (Sikh temple) in those days was in Stockton, over 100 miles away, in contrast to today, when the Bay Area alone has over a dozen gurudwaras and counting.

The First Ten Years: 1967–1977

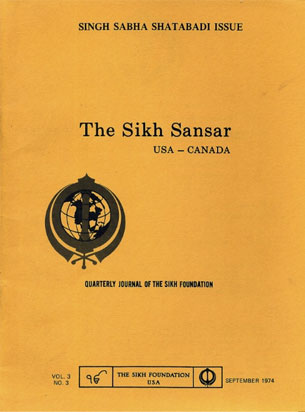

Soon after its establishment, the Sikh Foundation launched its initial publication, The Sikh Sansar, a quarterly journal, in 1972. The maharaja of Patiala, Sir Yadavindra Singh, and S. Hardit Singh Malik were its first patrons. The editorial board was composed of Dr. N. S. Kapany himself, Dr. R. K. Janmeja Singh, Prof. Hari S. Everest, Dr. Gurnam S. S. Brard, Prof. Harbans Lal, and Mrs. Satinder K. Kapany. An editorial advisory board was formed, attracting eminent scholars and writers such as Prof. W. H. McLeod, Prof. N. G. Barrier, Dr. M. S. Randhawa, Prof. Ganda Singh, Dr. Kartar S. Lalvani, Prof. Harbans Singh, Prof. Harbhajan Singh, and Khuswant Singh. The journal focused on many topics of interest to Sikhs, including Sikh Women, Sikh Educational Institutions, the Ghadar Movement, the American Bicentennial, Bhai Vir Singh, and many others. One special edition that stands out focused on Sikh Art, published in 1975. The term “Sikh Art” was introduced in that journal. Prof. R. P. Srivastava, head of the Department of Fine Arts, GCW Patiala-Punjab, stated the following in his guest editorial column: “For the first time in the history of journalism a systematic attempt is being made to record the significant contributions made by Sikh artists, sculptors, architects and artisans in the Punjab and elsewhere.” He further wrote, “No concerted effort was ever made by any Author or Historian and so far no one has tried to write anything on this aspect of achievement of the Sikhs which has glorified the pages of Sikh history and beautified the Punjab with architectural monuments.”

Looking back from now to this momentous beginning in 1976, it is clear that nothing less than a mind shift has been accomplished. In recent years Sikh Art has been celebrated by museums worldwide, including the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, and the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, among many others. Today there are over a dozen high-quality books on Sikh Art, written by art historians and scholars on areas ranging from textiles to paintings, from ancient manuscripts to contemporary art.

Growing up in the Punjab region of India, Narinder Kapany had often heard his grandmother recite stories of Guru Nanak’s life from their family’s manuscript of the Janamsakhis. This 19th century volume, richly illustrated with 40 colored plates (decades later donated to the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco), was his introduction to the beauty and richness of the art of his Sikh heritage and community. Having this beautiful manuscript in the family encouraged him and his young wife to become ardent admirers, collectors, and preservers of Sikh Art. In fact, the Kapanys were artists themselves—Satinder an accomplished dancer and painter, and Narinder a groundbreaking sculptor. His works, imaginatively titled “Dynoptic Sculptures,” were exhibited at museums across America, including San Francisco’s famed Exploratorium.

The literary activities undertaken by the Sikh Foundation in its first decade also included publishing books and creating opportunities for the local Sikh community to hear from Sikh stalwarts like Prof. Gopal Singh and Prof. Ganda Singh, both of whom were invited to give lectures.

In the foundation’s early years, a young American scholar, Mark Juergensmeyer, met Dr. Kapany. He had studied in the Punjab, and believed that Sikhism had a great deal to offer the world and therefore should be taught at American universities. (The word “Sikh,” in itself means “disciple” or “student.”) And what better way to live this ideology, he thought, than to introduce Sikhism to students here in America? The Sikh Foundation organized a conference in Berkeley in 1976, inviting over a dozen scholars to discuss ways and initiatives of how this could be made a reality at American institutes of higher learning. Out of this conference came an important publication, Sikh Studies: Comparative Perspectives on a Changing Tradition, published in 1979 as part of the Berkeley Religious Studies Series. With this, the Sikh Foundation had in its first decade taken the pioneering lead to include Sikhs and their heritage within two of America’s most important institutions—museums and universities.

1978–1998

Throughout the 1970s, the Sikh community throughout the United States and Canada felt a growing awareness of the need for being represented in the two important fields of the arts and academia. That realization steered the Sikh Foundation to foster deep and meaningful engagements with these communities while continuing to work on exploring the potential of launching Sikh studies at several universities. Yet the course of history that was being set in motion in the Punjab, the Sikh homeland, engulfed all academic and artistic ambitions at the time. As the Sikh community in the West became acutely aware of the violent and tragic turmoil unfolding there, the Sikh Foundation heeded the need of the hour.

Therefore, in the spring of 1984, accompanied by 150 other prominent Sikh Americans, Dr. Kapany, as chairman of the Sikh Foundation, addressed the U.S Congress in Washington, D.C., informing its members of the dire situation in Punjab. They expressed their growing apprehension that the Golden Temple in Amritsar, deeply revered by the Sikhs, might be attacked. So the Sikh Foundation sent an urgent telegram to the Indian Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, and to India’s Ambassador to the U.S., K. Shankar Bajpai, advising strongly against such an attack. Yet tragedy could not be averted and the Golden Temple was attacked on June 1,1984, shattering the faith and hopes of Sikhs worldwide. Hundreds of lives were lost in this military operation, codenamed “Operation Bluestar.”

The Sikh Foundation continued in its efforts to inform the world of the reality on the ground in Punjab. It organized a group of some 20 U.S. senators who were willing to make a fact-finding trip to Punjab, but the group was refused visas by the Indian Government. Undeterred and pursuing every opportunity to make the American people aware of Sikhs and the injustices being meted out to their community, Dr. Kapany confronted the Indian Ambassador on American television about the tragic events. Going a step further, the Foundation published full-page announcements in leading newspapers in major American cities to educate the public about Sikhs and the heinous crimes being committed against their community and their sacred spaces. Dr. Kapany also traveled to Canada to make a presentation to the Canadian House of Representatives on the situation in Punjab.

Soon afterward, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her Sikh guards. In that tragedy’s aftermath, over 3,000 Sikhs were viciously killed in Delhi and other parts of India. Working with community leaders from coast to coast, including Ganga Singh Dhillon and Dr. Shamsher Singh Babra, numerous community meetings and rallies were organized. This was a time before the Internet, and there were very limited means by which the community could keep abreast of the developing situation. To bridge this gap, a weekly newspaper, The Sikh Times, started publication from Palo Alto, California. Reviving the literary focus of the Sikh Foundation, a conference at the University of California–Berkeley was organized in 1987.

The fires and bullets of “Operation Bluestar” destroyed large parts of the Golden Temple complex, including its toshakhana (treasury). Priceless manuscripts and valuable artworks, witness to centuries of Sikh heritage, were lost or stolen forever. Collectively, these tragic events created a rising consciousness about the importance of preserving Sikh Art and culture, a critical part of who Sikhs are. This applies not only to paintings, manuscripts, textiles, sculptures, coins, and stamps, but also to Sikh monuments and architectural spaces, which are in grave peril even today, in both India and Pakistan.

Perhaps these events played a role in encouraging the Kapanys to actively start looking for and collecting Sikh Art, which today is renowned the world over. It includes masterpieces like the portrait of Rani Jind Kaur, illustrated books like Emily Eden’s Portraits of Princes and People of India, personal articles of Maharaja Ranjit Singh such as his spectacular emerald ring, miniature paintings of the ten Sikh Gurus, and much more.

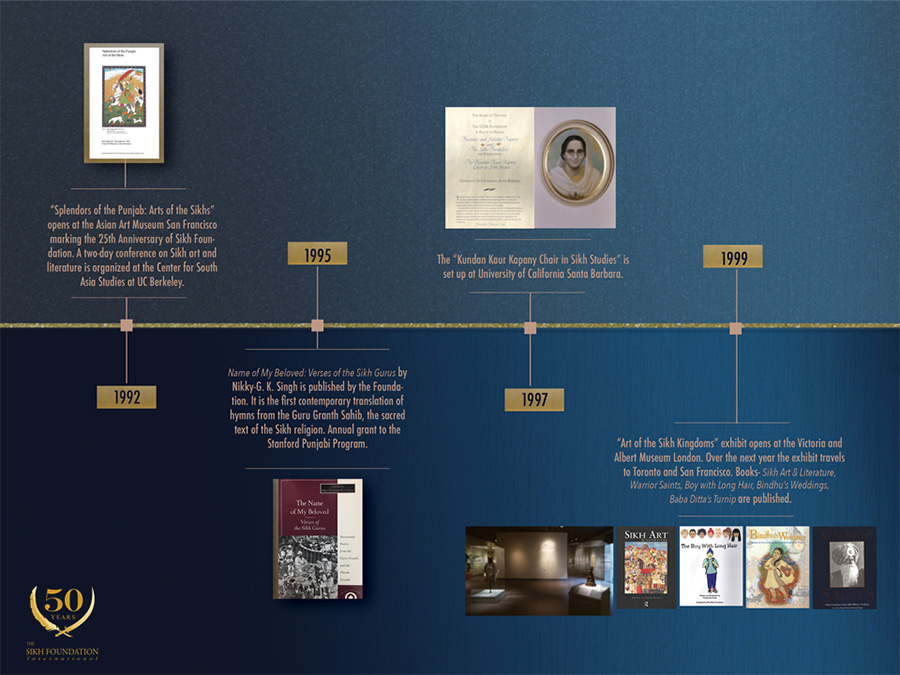

The 25th anniversary of the establishment of the Sikh Foundation presented a unique opportunity to share this growing Sikh Art collection with the world. Working with Forrest McGill, curator at San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum, the exhibit The Splendors of the Punjab: Art of the Sikhs opened there on November 25, 1992, accompanied by a grand Gala dinner. That was the first time that Sikh Arts were being celebrated at a leading American museum. Even more, this was a unique, collaborative partnership between academia and the arts. Alongside the exhibit, a two-day conference on “Sikh Art & Literature” was also held at the Center for South Asia Studies at UC Berkeley.

Meanwhile, a Punjabi language program had been started at Stanford University in 1986 with the initiative of a student, Harpal Singh Sandhu. Years later, in 1995 the Sikh Foundation stepped up to provide additional financial support to the program. Encouraging scholarship of the highest level, The Name of My Beloved: Verses of the Sikh Gurus, translated by Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh, was published in 1995. Khushwant Singh, the legendary author, wrote that it was “the first contemporary English translation of hymns from the Guru Granth Sahib—the principal sacred text of the Sikh religion—and the Dasam Granth, the poetry of the tenth Sikh guru. [It is] a significant contribution to the understanding of the essentials of the Sikhs’ sacred scriptures.”

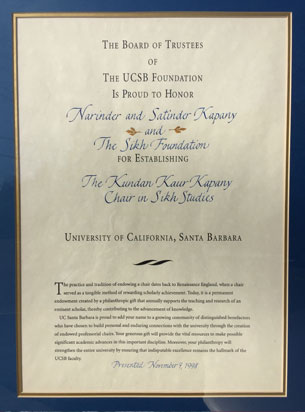

Mark Juergensmeyer, who in the early 1970s had introduced the idea of having Sikh Studies represented at universities, was now teaching at the University of California–Santa Barbara. This was the right time to turn dreams into reality. In 1997, the Kapanys established the “Kundan Kaur Kapany Chair in Sikh Studies” at University of California–Santa Barbara, in memory of Dr. Kapany’s mother. This academic chair was the first of its type in North America and paved the way for others to follow.

1999–2017

With these two firsts—the display of Sikh Arts at an American museum and the establishment of a Sikh Studies Chair at an American university—a new path for the future was laid. This was the culmination of the previous 30 years of work. It was also the beginning of a new future of a truly inclusive American society. It opened up a whole new world of possibilities for the Sikh community. The Sikh Foundation seized upon this opportunity and increased its efforts to further promote, preserve, and advance the artistic and academic study of Sikhism at the highest institutions of education and art.

With the idea of an international Sikh arts exhibit, Dr. Kapany approached curator Susan Stronge at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, one of the largest museums in the world, to make the dream a reality. Marking the tercentenary of the Khalsa, the “Arts of the Sikh Kingdoms” was opened by HRH The Prince of Wales on March 22, 1999. Nearly 300 works of art were displayed, ranging from a sleekly smithed cannon and turban-shaped helmets of damascened steel to rippling silks, Kashmir shawls, gem-encrusted jewelry, a golden throne, the earliest portraits of several Gurus, and court paintings of Sikh maharajas and noble warriors (Figs. 13 & 14). The exhibition was brought to the Asian Art Museum in September of that year, under the sponsorship of the Sikh Foundation. Its third and final destination was the Royal Ontario Museum, in (October 2000). More than half a million museumgoers viewed this exhibition in London, San Francisco, and Toronto.

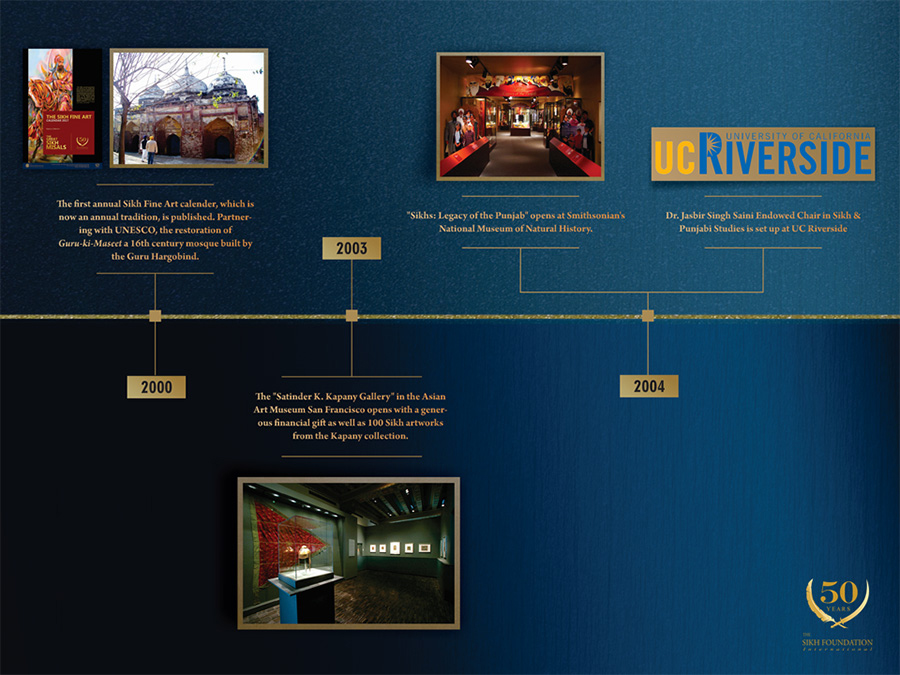

The Sikh Foundation was interacting with artists, scholars, and authors from around the world, leading to a number of high-quality publications. Written and richly illustrated with fascinating art by the “Singh Twins,” Amrit and Rabindra, the timeless classic Bindhu’s Weddings was published by the Foundation in 1999. That same year, Warrior Saints, by Amadeep Singh Madra and Parmjit Singh, and Pushpinder Kaur’s books The Boy with Long Hair and Baba Ditta’s Turnip were also published. In 2000, the Sikh Foundation brought out its first annual Sikh Fine Art Calendar, showcasing both contemporary and classic Sikh Art, becoming an annual tradition. The calendars have ever since been regarded as collector’s items and adorn homes and offices all over the world. At this time, efforts were also made in the field of monument conservation. Partnering with UNESCO, the partial restoration of a 16th century mosque, built by Guru Hargobind, was undertaken.

In 2001, the World Trade Center in New York City and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., were attacked by aircraft flown by Al Qaida terrorists, a horrific event that came to be known as 9/11. In its aftermath, Sikhs increasingly became the target of hate crimes all over the country, making the previous efforts of the Sikh Foundation even more relevant and meaningful. The need to educate Americans about Sikh culture, history, and religion became literally a matter of life and death.

In 2003, the Sikh Foundation celebrated its 35th Anniversary with the setting up of the Satinder Kaur Gallery at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. This is the first permanent gallery of Sikh Art in the West. Narinder and Satinder Kapany gifted 100 pieces of Sikh Art, including the 18th century Janamsakhi volume from which stemmed their love of art. The opening of the gallery was a moment of pride for the entire Sikh community, generating an appreciation of art’s ability to promote a better understanding of other cultures

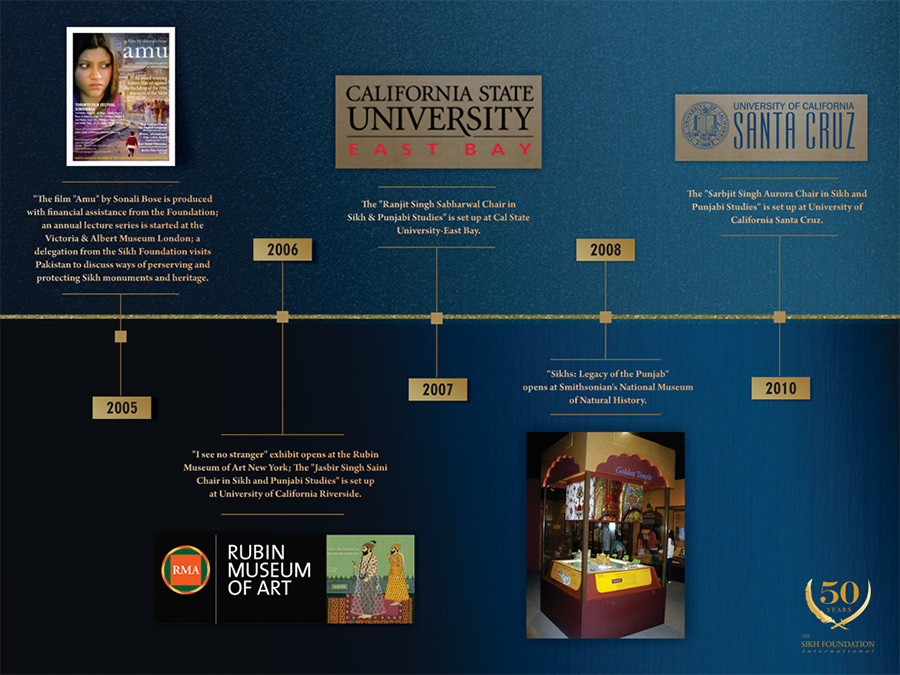

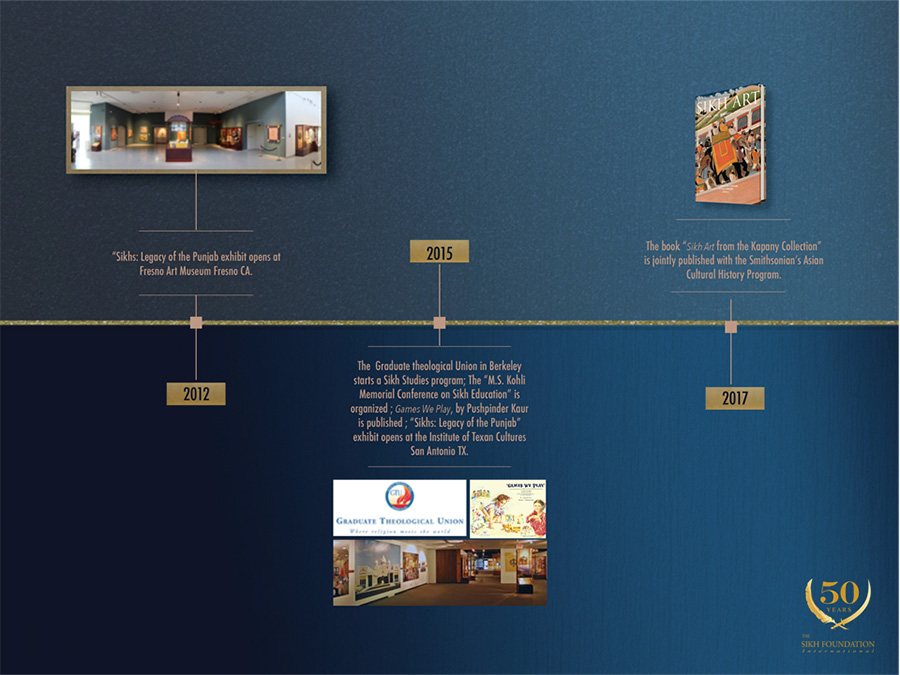

Community-led efforts were already under way at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., for a Sikh exhibit. Since the museum lacked any major Sikh Art collections of its own, Dr. Kapany readily agreed to loan a significant number of his personal artworks, to form the initial basis of the exhibit. On July 24, 2004, the National Museum of Natural History opened the exhibit “Sikhs: Legacy of the Punjab,” showcasing Sikh Art and Sikh cultural heritage. The exhibit later traveled to Santa Barbara, California (2008), Fresno, California (2012), and Dallas, Texas (2015).

In September 2006, the Rubin Museum of Art in New York City, with the support of the Sikh Art & Film Foundation and the Sikh Foundation, mounted an exhibit titled “I See No Stranger.” It brought together approximately 100 artworks that identify core Sikh beliefs and explore the plurality of cultural traditions reflected in both the objects and the ideals. The exhibit showcased Sikh Art from the 16th through the 19th centuries, including paintings, drawings, textiles, metalwork, and photographs.

During the same period, the Sikh Arts scene was gaining vibrancy internationally. At London’s Victoria & Albert Museum a Sikh Art Lecture series was launched in 2005, featuring acclaimed speakers and artists such as Dr. Susan Stronge, Dr. F. Aijazuddin, Arpana Caur, Gurinder Chadha who delivered talks on Sikh Arts and heritage. That same year, a delegation from the Sikh Foundation visited Pakistan. They toured Sikh heritage sites and met with various officials to discuss and explore ways of working together to preserve and protect Sikh monuments and heritage.

The success of the Kundan Kaur Kapany Chair in Sikh Studies at UC Santa Barbara (1999) encouraged the Sikh Foundation to encourage similar programs at other California campuses. The Dr. Jasbir Singh Saini Endowed Chair in Sikh and Punjabi Studies at University of California–Riverside (2006), the Ranjit Singh Sabharwal Chair in Sikh & Punjabi Studies at California State University–East Bay (2007), and the Sarbjit Singh Aurora Endowed Chair in Sikh and Punjabi Studies at UC Santa Cruz (2010) were set up by philanthropic Sikhs with the support of the community and the Sikh Foundation. In 2015 a Sikh Studies program was started at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley.

These endowed chairs and programs create a lasting legacy that will educate generations of students about Sikh culture and contributions. Recent world events illustrate the continued need for increased understanding of Sikh values, traditions, and contributions to the world. Such programs enable faculty and students alike to explore the culture, religion, history, literature, art, economics, language, politics, and contributions of the Sikhs from their origins in 16th-century Punjab to the present.

As a result of these and other efforts, numerous conferences, talks, and presentations have been arranged over the years. The MS Kohli Memorial Conference on Sikh Education at Stanford University (March 2015) engaged scholars, museums, and schools, along with several Sikh organizations, on ways to impact Sikh education. Talks by visiting scholars from the United States and abroad have enriched local communities, as have other events organized by the Sikh Foundation in past years.

As we look to the future, we will encounter many unknowns in the fields of education and art, especially in view of the lightning speed of change brought on by evolving technology in both spheres. So how will Sikh Studies evolve to take on the challenges of the future? How will Sikh Arts appeal to future generations? And how can the Sikh community’s connection with its own heritage be maintained? These are some of the challenging questions we think about as we celebrate 50 years of the Sikh Foundation and continue in our mission to inspire, educate, and engage communities around the world.

(This article is an updated version of the originally published (2017) three-part series. The author has sourced information from Sikh Foundation archives as well as interviews with Dr. N. S. Kapany.)

TIMELINE:

- 1967 – “Guru Gobind Singh—Reflections and Offerings” by Prof. Puran Singh published

- 1972–1977 – Sikh Sansar published (Sikh Art Issue, 1975)

- 1972 – “Sikhs in the USA & Canada” directory published; Dynoptic Sculptures exhibit, San Francisco Exploratorium

- 1974 – “The Sikhs and Their Religion” by Prof. Ganda Singh published

- 1976 – Berkeley Sikh Conference

- 1979 – Sikh Studies: Comparative Perspectives on a Changing Tradition published (Berkeley Religious Studies Series, 1979)

- 1984 – Sikh Times newspaper published; Full page advertisements in leading American newspapers; Community organizing in response to targeted violence toward Sikhs in India

- 1992 – 25th Anniversary of Sikh Foundation; “Splendors of the Punjab: Arts of the Sikhs” exhibited at San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum; 2-day conference “Sikh Art & Literature” at Center for South Asia Studies at UC Berkeley

- 1995 – Stanford Punjabi Language Program

- 1995 – Name of My Beloved by Dr. N. G. K. Singh published

- 1997 – Kundan Kaur Kapany Endowed Chair of Sikh & Punjabi Studies at UC Santa Barbara established

- 1999 – “Arts of the Sikh Kingdoms” exhibited at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London; publication of the books Sikh Art & Literature, The Boy with Long Hair, Bindhu’s Weddings, and Warrior Saints

- 2000 – First Sikh Fine Art Calendar published; Restoration project with UNESCO of Guru ki Maseet; “Arts of the Sikh Kingdoms” exhibited at the Asian Art Museum San Francisco

- 2003 – Satinder Kaur Kapany Gallery of Sikh Art established at the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco

- 2004 – “Sikhs: Legacy of the Punjab” exhibit opens at the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; Dr. Jasbir Singh Saini Endowed Chair of Sikh & Punjabi Studies established at University of California–Riverside

- 2005 – Film Amu released; Annual Lecture series started at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London; Pakistan Sikh Heritage tour

- 2007 – Dr. Ranjit Singh Sabharwal Endowed Chair in Sikh & Punjabi Language Studies established at California State University – East Bay

- 2008 – “Sikhs: Legacy of the Punjab” exhibit opens at Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History

- 2010 – The Sarbjit Singh Aurora Endowed Chair of Sikh & Punjabi Language Studies established at UC Santa Cruz

- 2012 – “Sikhs: Legacy of the Punjab” exhibit opens at Fresno Art Museum, California

- 2015 – Sikh Studies program started at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley; Conference on Sikh Education; Games We Play published; “Sikhs: Legacy of the Punjab” exhibit opens at the Institute of Texan Cultures, Dallas, Texas

- 2017 – 50th Anniversary celebrations of the Sikh Foundation at the Asian Art Museum and at Stanford University; Sikh Art from the Kapany Collection published